The New Bath Guide by Christopher Anstey

- Letter I l. 48-103

- Letter IV l. 44-61

- Letter V l. 35-67

- Letter VI l. 38-57

- Letter VII l. 41- 44

- Letter IX l. 8- 14

- Letter XIII l. 29-62

- Letter XV l. 77-92

- Christopher Anstey

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

Christopher Anstey, 1724-1805, with his daughter Mary

Portrait by William Hoare, c. 1779

Oil on canvas, 126 x 99.7 cm

National Portrait Gallery at Beningbrough Hall

He lived at N°6 Royal Crescent.

Christopher Anstey’s satire of Bath in The New Bath Guide

Christopher Anstey’s publication of The New Bath Guide in 1766 was an instant success. Yet, the very title of the book was misleading, as guidebooks proliferated, particularly those on Bath, which had, in 1766, reached the apex of its fame.

THE

NEW BATH GUIDE:

OR,

M E M O I R S of the B — R — D F A M I L Y.

In a SERIES of

POETICAL EPISTLES.

Nullus in orbe locus Baiis praelucet amoenis. HOR.

Sold by J. DODSLEY, in Pall-Mall; J. WILSON & J. FELL, in Pater- noster-Row; and J. ALMON, in Piccadilly, London; W. FREDERICK, at Bath; W. JACKSON, at Oxford; T. FLETCHER & F. HODSON, at Cambridge; W. SMITH at Dublin; and the Booksellers of Bristol, York, and Edinburgh. 1766.

The New Bath Guide (see Christopher Anstey, The New Bath Guide, Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Annick Cossic, Bern: Peter Lang, 2010) is a series of satirical letters written in verse by various members of a provincial family, the B-N-R-Ds or Blunderheads, who have come to Bath for therapeutic reasons: http://www.peterlang.com/index.cfm?...

Letter I l. 48-103:

For Lady B—N—R—D, my Aunt,

Herself propos’d this charming Jaunt,- All from Redundancy of Care

For SIM, her fav’rite Son and Heir:

To him the joyous Hours I owe

That Bath’s enchanting Scenes bestow;

Thanks to her Book of choice Receipts,- That pamper’d Him with sav’ry Meats;

Nor less that Day deserves a Blessing

She cramm’d his Sister to Excess in:

For now she sends both Son and Daughter

For Crudities to drink the Water.- E’er form’d a Set of stranger Wretches,

I own, my Dear, it hurts my Pride,

To see them blund’ring by my Side;

My Spirits flag, my Life and Fire

Is mortify’d au Desespoir,- When SIM, unfashionable Ninny,

In Public calls me Cousin Jenny;

And yet, to give the Wight his Due,

He has some Share of Humour too,

A comic Vein of pedant Learning- His Conversation you’ll discern in,

The oddest Compound you can see

Of Shrewdness and Simplicity,

With nat’ral Strokes of aukward Wit,

That oft, like Parthian Arrows hit,- For when He seems to dread the Foe

He always strikes the hardest Blow;

And when you’d think He means to flatter,

His Panegyrics turn to Satire:

But then no Creature you can find- Knows half so little of Mankind,

Seems always blund’ring in the dark,

And always making some Remark;

Remarks, that so provoke one’s Laughter,

One can’t imagine what he’s after:- And sure you’ll thank me for exciting

In SIM a wondrous Itch for Writing;

With all his serious Grimace

To give Descriptions of the Place.

No Doubt his Mother will produce- His Poetry for gen’ral Use,

And if his Bluntness does not fright you,

His observations must delight you;

For truly the good Creature’s Mind

Is honest, generous, and kind:- If unprovok’d, will ne’er displease ye,

Or ever make one Soul uneasy.—

I’ll try to make his Sister PRUE

Take a final Trip to Pindus too.

The textual superiority of the male viewpoint implies a predominantly masculine perception of Bath’s changing social scene. The book provides a prime example of “progress poetry”: as a long poem, it records the evolution of these three scions of the landed gentry who will leave Bath notably changed for the worse. Encapsulating the characteristics of the sermo and the epistula it traces the confrontation of the individual with the world. This “travelling family” has embarked on a pilgrimage, whose physical dimension eventually gives way to a spiritual one. The letters, which are journalistic, are turned towards the outside world, and very rarely have an introspective dimension. They either provide a eulogy of Bath, in Jenny’s case, or, more often than not, a stinging critique of the spa and of its spa attributes.

Theatricality and ritualisation

The characters’ progress unfolds against a theatrical backdrop, the new Bath scene. The city has undergone a complete architectural metamorphosis under the aegis of the Woods. Anstey anchors the poem in a historical reality –he historicizes the narrative. Each of Bath’s architectural wonders is described, in particular, The Parades (Letter I), the King’s Bath (Letter VI), the Assembly Rooms (Letter VIII, Letter X), Spring Gardens (Letter XIII). The selection of emblematic places answers two criteria, namely novelty and popularity, and follows the axes of Bath’s recent socio-economic development, i.e. therapy, leisure and fashion.

The letters, in fact, stage incidents, like Letter IV, A Consultation of Physicians: see Spas in Britain and in France, ed. Patrick Galliou & Annick Cossic (CSP, 2006).

Letter IV l. 44-61:

So thus they brush’d off, each his Cane at his Nose,

- And out of the Window she flung it down souse,

As the first Politician went out of the House.

Decoctions and Syrups around him all flew,

The Pill, Bolus, Julep, and Apozem too;

His Wig had the Luck a Cathartic to meet,- And squash went the Gallipot under his Feet.

She said ’twas a Shame I should swallow such Stuff

When my Bowels were weak and the Physic so rough;

Declar’d she was shock’d that so many should come

To be doctor’d to Death, such a distance from Home,- At a Place where they tell you that Water alone

Can cure all Distempers that ever were known.

Jenny exposes the dishonesty of the doctors and the formation of networks of physicians, apothecaries and nurses all bent on exploiting the gullibility of their patients.

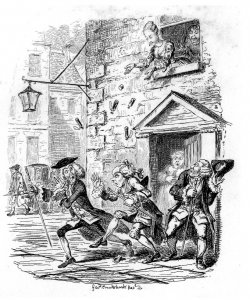

“The Doctors flying from their own physic” (George Cruikshank)

Letter V l. 35-67:

For when we arriv’d here at Bath t’other Day,

They came to our Lodgings on Purpose to play:

And I thought it was right, as the Music was come,

To foot it a little in TABITHA’s Room,

For Practice makes perfect, as often I’ve read,- And to Heels is of Service as well as the Head;

But the Lodgers were shock’d such a Noise we should make,

And the Ladies declar’d that we kept them awake;

Lord RINGBONE, who lay in the parlour below,

On Account of the Gout he had got in his Toe,- Began on a sudden to curse and to swear,

I protest, my dear Mother, ’twas shocking to hear

The Oaths of that reprobate gouty old Peer:

“All the Devils in Hell sure at once have concurr’d

“To make such a Noise here as never was heard,- “Some blundering Blockhead, while I am in Bed,

“Treads as hard as a Coach-Horse just over my Head;

“I cannot conceive what a Plague he’s about,

“Are the Fidlers come hither to make all this Rout

“With their d-mn’d squeaking Catgut that’s worse than the- “Gout?

“If the Aldermen bad ’em come hither, I swear

“I wish they were broiling in Hell with the May’r;

“May Flames be my Portion if ever I give

“Those Rascals one Farthing as long as I live.”—- So while they were playing their musical Airs,

And I was just dancing the Hay round the Chairs,

He roar’d to his Frenchman to kick them down Stairs.

The Frenchman came forth with his outlandish Lingo,

Just the same as a Monkey, and made all the men go:- I could not make out what he said, not a Word,

And his Lordship declar’d I was very absurd.

The ritual devised by Beau Nash in order to regulate Bath’s social life fuels the plot, as in letter V, when the musicians that greet the newcomers on their arrival in Bath are thrown out by one of Simkin Blunderhead’s neighbours, thus contrasting the ideal of social harmony with the ill-temper and exasperation of the individual.

“Simpkin dancing to the Musicians” (George Cruikshank).

The incidents all follow a binary pattern of happiness and unhappiness and testify to the difficulty for an individual to fit into a new society, with its new social codes. The letters actually stage contemporary issues, illustrated by the misfortunes of a specific family. The new society includes a new social structure where the middling orders are slowly gaining the upper ground. The members of the landed gentry find themselves squeezed between upwardly mobile tradesmen and a still powerful aristocracy, as exemplified by the row with Lord Ringbone (Letter V). The issue of status features prominently in the book, as well as that of the new drug culture, particularly noticeable in a spa like Bath.

The indictment of a new sociability

Anstey’s poem outlines a map of sociability through the satire of public places like the Pump Room, the King’s Bath, the Ball Room, the Spring Gardens, or of the new residential buildings such as Queen Square, the King’s Circus, and the Royal Crescent, not yet completed.

Letter VI l. 38-57:

And of all the fine Sights I have seen, my dear Mother,

I never expect to behold such another:- How the Ladies did giggle and set up their Clacks,

All the while an old Woman was rubbing their Backs!

Oh ‘twas pretty to see them all put on their Flannels,

And then take the Water like so many Spaniels,

And tho’ all the while it grew hotter and hotter,- They swam, just as if they were hunting an Otter;

’Twas a glorious Sight to behold the Fair Sex

All wading with gentlemen up to their Necks,

And view them so prettily tumble and sprawl

In a great smoaking Kettle as big as our Hall:- And To-Day many Persons of Rank and Condition

Were boil’d by Command of an able Physician,

Dean SPAVIN, Dean MANGEY, and Doctor DE’SQUIRT,

Were all sent from Cambridge to rub off their Dirt;

Judge SCRUB, and the worthy Counsellor PEST- Join’d Issue at once, and went in with the rest:

And this they all said was exceedingly good

For strength’ning the Spirits, and mending the Blood.

Letter VII l. 41- 44:

The Loungers are come too.− Old STUCCO has just sent

His Plan for a House to be built in the Crescent;

’Twill soon be complete, and they say all their Work

Is as strong as St. Paul’s, or the Minster at York.

Letter IX l. 8- 14:

How Pleasure wastes the various Day:

Whether thou art wont to rove- By Parade, or Orange Grove,

Or to breathe a purer Air

In the Circus or the Square;

Wheresoever be thy Path,

Tell, O tell the Joys of Bath.

Letter XIII l. 29-62:

Now my Lord had the Honour of coming down Post,

- To pay his Respects to so famous a Toast;

In Hopes He her Ladyship’s Favour might win,

By playing the Part of a Host at an Inn.

I’m sure He’s a Person of great Resolution,`

Tho’ delicate Nerves, and a Weak Constitution;- For he carried us all to a Place cross the River,

And vow’d that the Rooms were too hot for his Liver:

He said it would greatly our Pleasure promote,

If we all for Spring-Gardens set out in a Boat:

I never as yet could his Reason explain,- Why we all sallied forth in the Wind and the Rain?

For sure such Confusion was never yet known;

Here a Cap and a Hat, there a Cardinal blown:

While his Lordship, embroider’d, and powder’d all o’er,

Was bowing, and handing the Ladies ashore:- How the Misses did huddle and scuddle, and run;

One would think to be wet must be very good Fun;

For by waggling their Tails, they all seem’d to take Pains

To moisten their Pinions like Ducks when it rains;

And ’twas pretty to see how, like Birds of a Feather,- The People of Quality flock’d all together;

All pressing, addressing, caressing, and fond,

Just the same as those Animals are in a Pond:

You’ve read all their Names in the News, I suppose,

But, for fear you have not, take the List as it goes:- There was Lady GREASEWRISTER,

And Madam VAN-TWISTER,

Her Ladyship’s Sister.

Lord CRAM, and Lord VULTUR,

Sir BRANDISH O’ CULTER,- With Marshal CAROUZER,

And old Lady MOWZER,

And the great Hanoverian Baron PANSMOWZER, […].

In each letter, disorder is introduced into a well-regulated world where the Palladianism of the new buildings expresses the vision of a utopian society — articulated by the Woods — in which external order is conducive to internal harmony and virtue: see Annick Cossic, Bath au XVIIIe siècle. Les Fastes d’une cité palladienne (PUR, 2000). It is through burlesque and irony that Anstey debunks the new open society of the middle of the century. Donning the mask of Simkin, he takes the moral high ground and condemns the vices and follies of his contemporaries. His use of “deliberative satire” serves his moral purpose, which is to enlighten and to instruct through the pleasure brought by laughter. The use of indirection culminates in the “Epilogue,” officially meant to redeem the transgression of the letters, but actually fulfilling a very different function, namely that of the author’s self-justification.

EPILOGUE

TO THE

NEW BATH GUIDE.

CONTAINING,

CRITICISMS, and the GUIDE’s CONVERSATION with three

LADIES of Piety, Learning, and Discretion.

A Letter to Miss JENNY W—D—R at Bath, from Lady E—

M—D—SS, her Friend in the Country; a young Lady of

neither Fashion, Taste, nor Spirit.

The CONVERSATION continued — Their LADYSHIPS Receipt for a

NOVEL. — The GHOST of Mr. QUIN.

The New Bath Guide is transgressive in so far as it questions the apparent consensus that fostered a new type of sociability at odds with the ideal of retirement conducive to spleen or the result of the English Malady. Transversales 1. (Le Manuscrit, 2012) Transversales 2 (Le Manuscrit, 2013).

Anstey’s satire is more devastating than it seems, and the alternation of images of darkness and of brightness constantly reminds the reader of his postlapsarian condition. Laughter is but part of the use of disguise throughout the poem, including its Epilogue, added in the second issue of the First Edition. Anstey, as a true satirist, exposes the monstrosity of Bath, the superficiality of the aesthetics of novelty developed by the city’s architecture and consumer society. By so doing, he runs the risk of turning his mouthpiece, Simkin, into an object of hatred and rejection, and himself into a monster (see Michael Seidel, Satiric Inheritance, Rabelais to Sterne [Princeton UP, 1979]). The punitive intent of the satirist is obvious in the fate of the letter-writers whose only salvation lies in their return to their provincial homes:

Letter XV l. 77-92:

Now they say that all People, in our Situation,

Are very fine Subjects for Regeneration:

But I think, my dear Mother, the best we can do,

Is to pack up our All, and return back to you.Farewell then, ye Streams,

Ye poetical Themes!

Sweet Fountains for curing the Spleen!

I’m griev’d to the Heart,

Without cash to depart,

And quit this adorable Scene.Where gaming and Grace

Each other embrace,

Dissipation and Piety meet:——- May all, who’ve a Notion

Of Cards or Devotion,

Make Bath their delightful Retreat.S. B———D.

FINIS.

Anstey’s portrait of Bath and of Bath characters is truly ambiguous, since his awareness of the beauty of the place does not preclude the expression of his great reservations about the new economic development of a modern leisure-oriented spa.

Beyond his critique of spa life, it is the emergence of a new model of sociability, resulting from several factors – political, economic and sociological – partly imported from London, but in many respects created in Bath, that he records with strong misgivings.