Crime in London

Crime statistics

A table of the charges brought in Middlesex felony cases, drawn from “Middlesex felony cases” hard at the Old Bailey from May 1719 to April 1722

| assault and theft | 7 |

| burglary | 21 |

| fraud | 1 |

| highway robbery | 11 |

| misc | 11 |

| murder | 12 |

| pickpocket | 23 |

| receive stolen goods | 20 |

| theft | 168 |

A table of the punishments meted out to convicted felons, drawn from “Middlesex felony cases”

| Null Value | 175 (no information on outcome, possibly trial dropped) |

| benefit of clergy | 23 |

| branding | 6 |

| hanging | 25 |

| jail | 2 |

| transportation | 41 |

| whipping | 2 |

A table of the ranges of crimes inmates of the Westminster house of correction were convicted of, divided by sex, and drawn from “Westminster House of Correction”

| Female | Male | Unknown | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loose, idle and disorderly | 77 | 8 | 8 |

| Miscellaneous | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Property | 35 | 11 | 1 |

| Prostitution | 64 | 1 | 2 |

| Service | 2 | 4 |

In Tim Hitchcock and Robert Shoemaker, Economic Growth and Social Change in the Eighteenth-Century English Town (TLTP CDRom, Glasgow, 1998)

Early 18th-century London prisons

- Prison Scene

- William Hogarth, The Prison Scene from The Rake’s Progress (1735)

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

In the early 18th century, prisons held two major categories of inmates: debtors (and their families) hounded by their creditors, and offenders awaiting judgment or execution. Prison sentences were not prescribed as a form of long-term punishment. Before 1750, the existing prisons in London offered neither enough space nor security. The sanitary conditions were appalling, and inmates were often the victims of epidemics of what was then called “jail fever” (a form of typhoid). Food, water and candles had to be purchased by the prisoners. The jailers were often corrupt, and only those inmates who could pay for “garnish” could hope to be treated without cruelty, as John Gay suggested in The Beggar’s Opera (1728). Spirits were on sale in all prisons, visitors came and went, and considerable disorder and violence reigned.

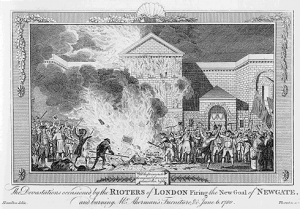

Prison buildings in London

- Newgate prison

- Newgate prison set on fire, with the Keeper’s furniture burnt in the street during the Gordon Riots in 1780 (design by Hamilton, engraving by Thornton)

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

Newgate prison, in the heart of the City, had been rebuilt after the great Fire of 1666, but was almost immediately overcrowded. It was notoriously unhealthy, and one can easily understand why the heroine of Defoe’s Moll Flanders (1722) was so terrified when she was sent there:

’ Tis impossible to describe the terror of my mind, when I was first brought in, and when I look’d round upon all the horrors of that dismal Place: I look’d on myself as lost, and that I had nothing to think of, but of going out of the World, and that with the utmost Infamy; the hellish Noise, the Roaring, Swearing and Clamour, the Stench and Nastiness, and all the dreadful croud of Afflicting things that I saw there; joyn’d together to make the Place seem an Emblem of Hell itself, and a kind of Entrance into it.

Newgate was entirely rebuilt in the 1770s to the designs of George Dance the Younger, but almost immediately ravaged by fire during the antiCatholic Gordon Riots (1780), which allowed the prisoners to escape. The reconstructed building (by the same architect) had a sombre Piranesian facade, which served as a backdrop for public executions, transferred here from Tyburn in the 1780s.

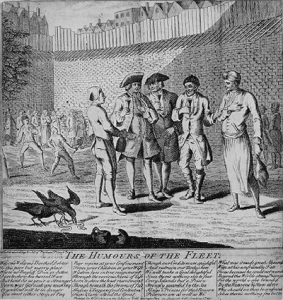

- The Fleet Prison

- The keeper of the Fleet Prison drinking with debtors (engraved frontispiece of W. Paget’s The Humours of the Fleet, London, 1749)

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

The Fleet Prison, standing on the bank of the Fleet River, accommodated many debtors, who were often charged extortionate prices for bed and board by keepers. The scandal rose to such a pitch that in 1729 a Parliamentary committee of enquiry was called. It was revealed that Thomas Bambridge, the head keeper, “had arbitrarily and unlawfully loaded with irons, put into dungeons, and destroyed prisoners for debt, under his charge, treating them in the most barbarous and cruel manner”. Like Newgate, the Fleet Prison was burnt down in 1780 during the Gordon Riots. Even reconstructed, the prison remained crowded, riotous and dirty.

The King’s Bench Prison, on the South Bank, also accommodated many debtors. It was rebuilt in the 1750s in St George’s Fields as a large block with 224 rooms. The wealthier prisoners were allowed to buy ’freedom of the Rules’, i.e. to live in the vicinity of the prison. Among its illustrious inmates were Pascal Paoli, the ’King’ of Corsica, and the novelist Tobias Smollett, both imprisoned for debt. The latter even managed to write his novel Sir Lancelot Greaves while in prison.

The keeper of the Fleet Prison drinking with debtors (engraved frontispiece of W. Paget’s The Humours of the Fleet, London, 1749)

John Howard and the reform of prisons

John Howard (1726-1790) was a man of non-conformist background, who, as high sheriff of Bedfordshire (1773), had inspected a number of country prisons and been shocked by their inadequacy. He participated in the drafting of the Gaol Distemper Act of 1774, which prescribed proper ventilation, regular cleaning and whitewashing of prisons, but was unfortunately seldom applied. Howard’s report first published as The State of the Prisons in England and Wales ( 1777) was a detailed indictment of the conditions under which prisoners were interned. He found that half of them were not criminals but debtors. In his book, he denounced the poor sanitary conditions, the inadequate architecture and the rapacity of jailers. Some of his recommendations, however, were highly debatable, such as the ’solitary silent system’ for the more rebellious prisoners. In any case, it took a long time before prison reform actually took place. Millbank prison, in Westminster, was the first ’modern’ prison of the early 19th century, opened in 1817 at a cost of £450,000, and designed according to a radial plan. At least it provided well ventilated buildings, with characteristic long naves with open balconies, still found today in the older prison buildings.